What’s next for museum education?

One of the most prominent activities of any museum is its education programming. ‘Learning’ is big business in the heritage sector and its profile has increased enormously in recent years. Any development project wanting to attract large sums of money has to demonstrate to its funders that there will be some educational benefit to visitors and to specified communities. The heritage education sector has come on leaps and bounds in the last ten years. But where is it going next?

Museum education is more than the simple advancement of knowledge. Education officers don’t simply show kids around museums and hand out worksheets. They create comprehensive, engaging learning programmes that include on- and off-site interaction relevant to the curriculum and – in the most part – free to schools. They create learning environments which enable young people to interact and to understand and, hopefully, take away the idea that museums are not ageing places full of dusty specimens, but lively sources of knowledge, inspiration and creativity.

Museum education is more than the simple advancement of knowledge. Education officers don’t simply show kids around museums and hand out worksheets. They create comprehensive, engaging learning programmes that include on- and off-site interaction relevant to the curriculum and – in the most part – free to schools. They create learning environments which enable young people to interact and to understand and, hopefully, take away the idea that museums are not ageing places full of dusty specimens, but lively sources of knowledge, inspiration and creativity.

This hasn’t happened overnight

Since 1997 the heritage sector has seen a host of new opportunities created for learning in the arts.

In the last decade museums have:

... figured out how to measure learning

Well, we’ve had a good go at it, anyway. The sector now uses the Inspiring Learning for All framework as a standard and terms such as Generic Learning Outcome or Generic Social Outcome are universally understood across the board.

... increased access to collections by reaching out to people

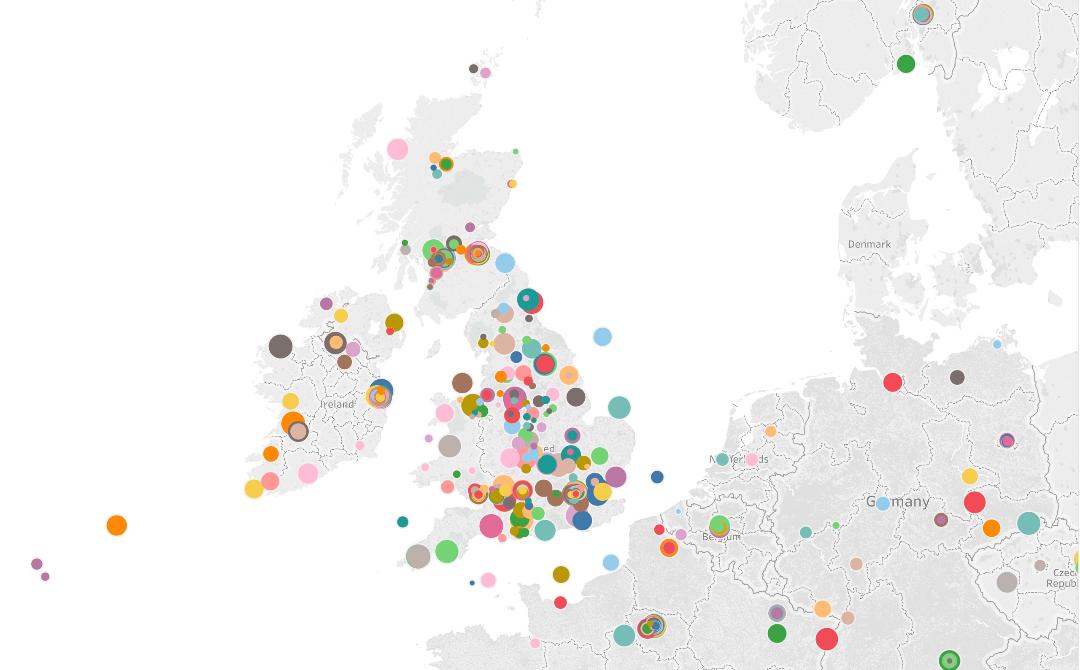

Outreach projects have taken place in schools, loan boxes of handling objects have been sent across the nation and heritage venues have are skyping with young people across the world.

... thought a lot about audiences and how to get them into museums

New and innovative audience development programmes have sought to plug the diversity gap in our nations museums. We might not have necessarily found the key to permanent shifts in cultural diversity, but we’ve started taking steps in the right direction.

... built new education spaces

No new or developed museum is without a Clore Education centre or other space used for delivering formal learning. These spaces are often state-of-the-art with interactive white boards and video-conferencing facilities.

... further professionalised the museum education sector

We’ve upped the standard of professional development for education professionals with new training and development schemes both within museums and as a sector. University courses and postgraduate degrees are more commonplace, as is attendance at conferences and training days.

So, with all this work underway in the ever-growing sector of heritage education, one might ask the question ‘what’s next?’ Where is museum education in the UK going? What are we going to be talking about over the next few years? When it comes to heritage education, what are the stories that are going to dominate the museum press?

What might be next?

Are we going to perhaps have an online learning revolution? Will the little black and silver boxes with apples on that we carry around with us act as a catalyst for museums thinking in new ways about how handheld technology works as part of a museum visit? Will museums work increasingly as part of public private partnerships?

Perhaps we’ll not have time for any of this – instead we could simply be worrying about money?

Or are we finally going to get to grips with audience development? Museums have shown in the last few years that they can get bums on seats as and when sponsorship deals require it – for an exhibition or a public programme relevant to a specific audience. But once the HLF money has run out and the museum in question moves on to another subject that project-originated relationship dies a death and the new audience becomes disenfranchised. Perhaps the biggest challenge for learning and access teams across the country is how to build sustainable relationships.

We could be going just about anywhere. Museum [Insider] spoke with three leading commentators in the heritage field to find out what they think.

Gillian Wolfe CBE (Director of Learning at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London) hopes to see a greater emphasis on the social impact of museums.

‘Where we see the future for our own education programme is in redefining our role within the community.

The transformative nature of the arts is so well proven in many of our social programmes that this is the way we want to develop. In a way it is to do with connecting with society in a way far beyond the affect of an exhibition.

Building on our experience of many years we know that it takes consistent commitment to change lives, particularly of those not predisposed to visit an art gallery or museum. Box ticking short programme funding is not useful. Regular interaction over several years is the effective way to build up a reputation for trust and to involve new audiences.

We also hope to develop research-based programmes that prove the social and health benefits of the arts.’

Samantha Heywood (Director of Learning and Interpretation, Imperial War Museum, London) predicts a technological shift.

‘The next big thing in museum education has to be something about integrating the real with the digital, to produce experiences that have genuine learning processes and fun embedded in them and require an interaction with real objects, places or people to actually make sense.

How this manifests itself will remain to be seen. It's got to be a blend or hybrid of all the technical possibilities that we have now, but used in a different way and more intelligently. Something that blurs the boundaries between being in the museum and being at home, but that gains greater depth and excitement when in the museum.’

The final phase of Samantha’s project Their Past Your Future involved using social media technology for learning in a museum context. Kids were organising and reporting on their own learning as they went using the radio waves software. Sam continues:

‘There's definitely more to be done along these lines. We were using essentially very simple equipment and software - but I wonder if we can get to the point where, by using more cutting edge software, we'd move it on to another level.

‘I also wonder when we'll start integrating good user-generated content in our galleries. I'm really keen to explore this for the redevelopment of the [new] galleries [at Imperial War Museum London]. We ought to provide some living 'proof' of how history is still relevant to people today.’

Viv Golding (Lecturer at the University of Leicester’s Department of Museums Studies) has written about just this subject recently.

‘In my book Golding, V, 2009, Learning at the Museum Frontiers: Identity, Race and Power (LMF) I outline some key challenges facing museums in the future decade. Overall I argue for the social role of the museum to be progressed, with a strong focus on addressing issues of human rights, social justice together with their audiences. This builds on Duncan Cameron’s idea first mooted in the 1970s, of the museum as an active forum space for audiences to engage in dialogical exchange, rather than a passive temple space of cultural worship.

‘I expand upon Cameron with reference to the concept of the museum frontiers, which is conceived as a wider socio-cultural space beyond the walls of the building, where new identities more positive can be constructed and new alliances forged for the promotion of democracy and citizenship, through the mutual respect inherent in feminist-hermeneutic dialogue.

‘At the museum frontiers, while curators share authorial control with those outside of the institution, they do not abnegate their responsibility; on the contrary, they are deeply concerned with equality of opportunity, access and inclusion for all, alongside their academic areas of expertise.

‘Working together with communities on the interpretation of existing collections and the co-collecting of new ones, curators permit an expression of global and local identities, as fluid and shared across time and space. Collaborative work shows differences and similarities, to nurture more cohesive communities with a sense of common humanity and belonging.

‘My own work, for more than 10 years at the Horniman Museum, has demonstrated that this can be achieved by developing critical thought and empathy in audiences through multi-sensory techniques such as handling, which regard the mind and the body holistically. For example children working on an ‘Inspiration Africa!’ project did not simply acquiesce to the cultures and beliefs expressed by the African artists, but were empowered to criticize unacceptable sexist attitudes and tackle these with their teachers and museum staff in the spirit of the project as a whole. Similarly in Götenburg, Sweden at the Museum of World Culture the aim is for exhibitions to ‘develop an experimental and questioning style ... so that many different voices can be heard’, and at the District Six Museum in Cape Town creative curatorial techniques ensure that a multitude of voices may be heard, to further healing and reconciliation, following the terrible history of apartheid in South Africa.

‘In short, the role of the museum over the next 10 years is vast! I am optimistic about the future though.’

People who know about museum education

If you want to learn more about the heritage education sector, you’d do worse than getting in touch with the one or more of the following:

Group for Education in Museums (GEM) is a membership group for museum professionals and freelancers working in museum education.

Engage promotes excellence in visual arts learning in museums and galleries.

The Smithsonian has a special branch working in the field of museum education.

There’s also a great reading list about museum education on the V&A website: http://www.vam.ac.uk/about_va/whoswho/dept_learning/edu_reading_list/index.html

Author:

Steve Slack is a writer and researcher working in the cultural heritage sector

www.steveslack.co.uk